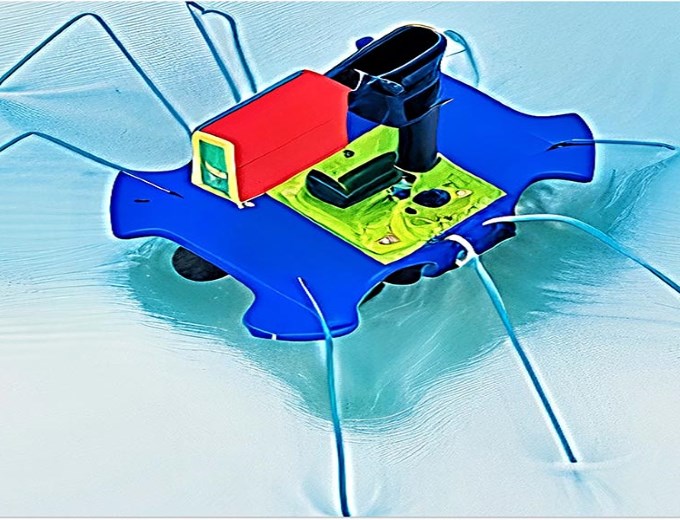

‘The Ocean of Things’: Self-powered robot bugs collect environmental data with aquatic IoT

31 July 2024

Image: Provided

A new bug-like robot, which is able to skim across water, is poised to revolutionise the field of aquatic robotics and enhance the capabilities of the Internet of Things (IoT) in water environments.

Futurists predict that more than one trillion autonomous nodes will be integrated into all human activities by 2035 as part of the Internet of Things. Soon, pretty much any object – big or small – will feed information to a central database without the need for human involvement.

Making this idea tricky is that 71 percent of the Earth's surface is covered in water, and aquatic environments pose critical environmental and logistical issues.

To consider these challenges, the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has started a programme called the Ocean of Things.

Over the past decade, Binghamton University Professor Seokheun "Sean" Choi – a faculty member at the Thomas J. Watson School of Engineering and Applied Science's Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and Director of the Center for Research in Advanced Sensing Technologies and Environmental Sustainability (CREATES) – has received research funding from the Office of Naval Research to develop bacteria-powered biobatteries that have a possible 100-year shelf life.

Choi, along with Anwar Elhadad, PhD '24, and PhD student Yang ‘Lexi’ Gao, developed the self-powered bug.

The new aquatic robots use similar technology because it is more reliable under adverse conditions than solar, kinetic or thermal energy systems.

A Janus interface, which is hydrophilic on one side and hydrophobic on the other, lets in nutrients from the water and keeps them inside the device to fuel bacterial spore production.

"When the environment is favourable for the bacteria, they become vegetative cells and generate power," he said, "but when the conditions are not favourable – for example, it's really cold or the nutrients are not available – they go back to spores. In that way, we can extend the operational life."

The Binghamton team's research showed power generation close to 1mW, which is enough to operate the robot's mechanical movement and any sensors that could track environmental data such as water temperature, pollution levels, the movements of commercial vessels and aircraft, and the behaviours of aquatic animals.

Being able to send the robots wherever they are needed is a clear upgrade from current ‘smart floats’, which are stationary sensors anchored to one place.

The next step in refining these aquatic robots is testing which bacteria will be best for producing energy under stressful ocean conditions.

"We used very common bacterial cells, but we need to study further to know what is actually living in those areas of the ocean," Choi said.

"Previously, we demonstrated that the combination of multiple bacterial cells can improve sustainability and power, so that's another idea.

“Maybe using machine learning, we can find the optimal combination of bacterial species to improve power density and sustainability."